|

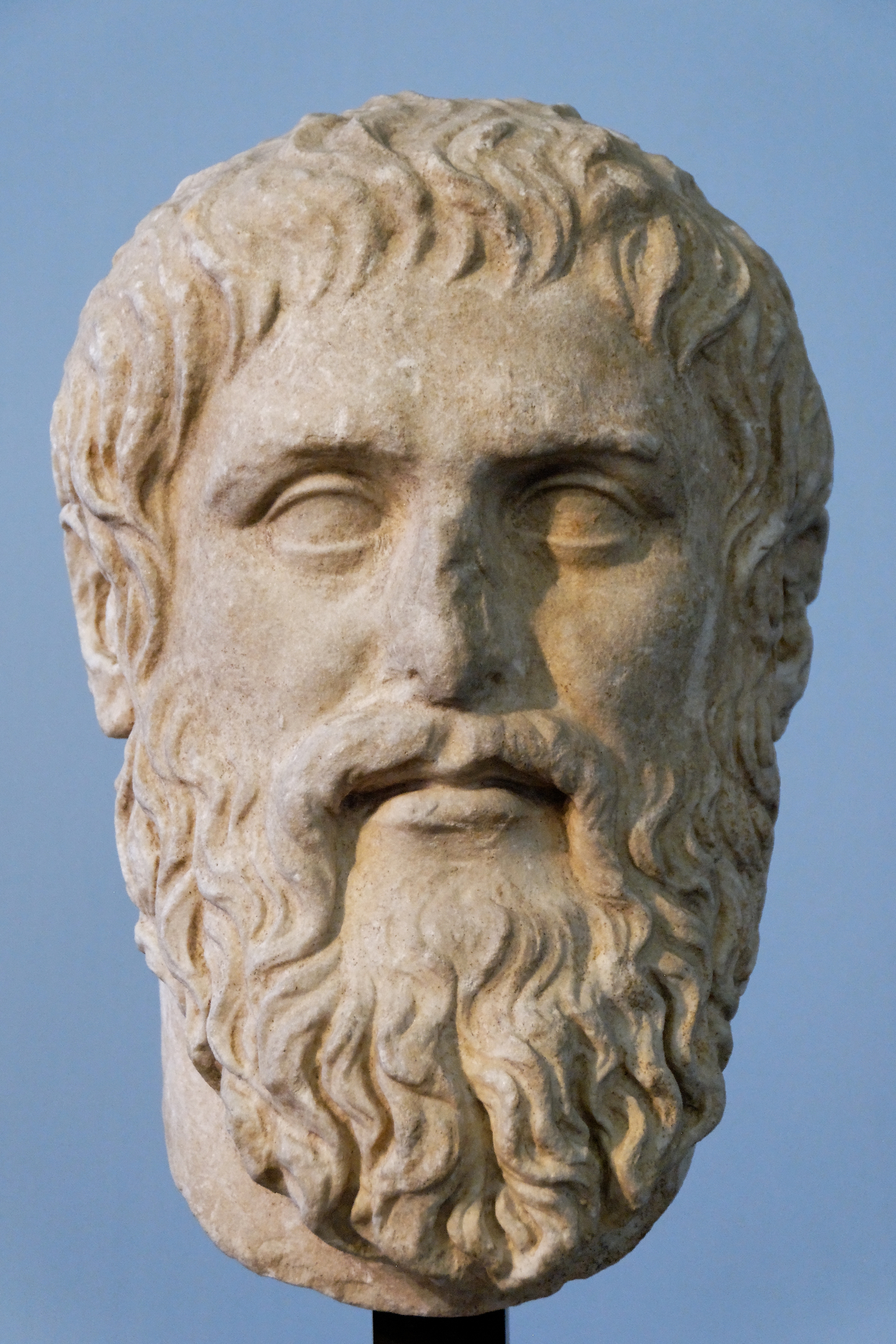

| image © Marie-Lan Nguyen Wikimedia Commons This post is part of a series on Plato's Republic. It can stand alone, but is intended to continue the line of thinking summarized here. |

In fact, if we follow up on Socrates's refutation as it is developed in the ensuing conversation with Cephalus's son, Polemarchus (not to mention Thrasymachus, we do find that benefit, especially with regard to the possibility of being mistaken about it, is a crucial turning point in the question about justice. According to Polemarchus, the hard cases of justice in which it supersedes the determinations of legal property are governed by the principle that "friends owe it to their friends to do good for them, never harm," and that justice "gives benefits to friends and does harm to enemies." So you would not give a deposited weapon back to an enraged friend because you know it would not benefit him but harm him to have it.

|

| I just can't think about the idea of the good when you look at me that way. |

Socrates's refutation of Cephalus does not turn explicitly on the question of benefit, but it does make clear that Cephalus cannot have seen the benefit of money, precisely in its relation to the idea of benefit, if he thinks that it facilitates justice by way of paying what is owed. For it equally facilitates injustice, if paying what is owed is sometimes unjust.

Thus the obstruction in Cephalus's view of the benefit of wealth is his own presumption of knowledge. He does not see benefit because he does not look for it in a place of darkness — in the field of his ignorance. Socratic wisdom is famously knowledge of ignorance. Here we see that this knowledge is a positive power, that orients the knower in the direction of what he would learn. To get the benefit of Cephalus's report, Socrates needs to place it in the light of something obscure. Benefit itself needs to be seen as something that somehow hides itself.

continued

On the list of things I hadn't planned on doing this semester, rereading the Republic used to be one of them?

ReplyDeletePerhaps this time through, the way into the riddle will produce greater clarity.

Please let me know if it does!

ReplyDeleteOnly read Book I this evening, and probably need to re-read, but your last two paragraphs lost me a little bit. I must confess, I was expecting something a bit more climactic after all this build-up. But let's see: Cephalus doesn't understand benefit because he thinks he knows what benefit is? His understanding is too morally ambivalent. (And "benefit" is such an elusive concept that we can almost assume someone is wrong who claims to know confidently what it is.) Enjoying reading your blog entries, even I'm stumbling along trying to understand ...

ReplyDeletePF: Sounds like you're keeping up just fine. I'm sure any stumbling is due to the littered and poorly lit corridors of my mind, not to any deficiency on your part. As for the "build-up," that's more like the plaque on my teeth than the development of a Bach fugue. There's just that much bad crap you have to scrape through to get to the truth.

ReplyDeleteI can see why my conclusion about the refutation of Cephalus might be disappointing. I think I need to hammer out a few distinctions to make it clear why I regard this conclusion as significant. I'll try to do that in a future post, but for now, let me sketch out a few things in outline.

1. The finding of the dialectic is not sufficiently identified as the ignorance of the interlocutor (my fault: I said that the obstruction was "his own presumption.") In order to count as dialectical (as defined in the more recent post "A Step Back: 'What is Dialectic?'"), the refutation has to open a view to a translation of multiplicity into unity (or vice versa), and this view has to be more truthful than the original. I see that I haven't explained how knowledge of ignorance can be more than just self-knowledge (e.g., knowledge of "one's own presumption"), nor how the refutation of Cephalus would illustrate this knowledge. That's a job for future posts, I guess.

2. Obscurity/ignorance is a more open-ended category than seeming/opinion. Thus the Socratic pattern of refutation engages in a dialog with the specific seeming/being interpretation of dialectic, criticizing its self-assured self-definition (without yet offering an alternative), even as it engages in more specific conversations with Socrates's interlocutors.

3. Cephalus's particular ignorance of benefit directly corresponds to his confidence in money's power to preserve benefit. I hope to draw this aspect of the pre-dialectical position more clearly in the discussion of Polemarchus (who at least at first is led to see justice as equivalent with value-neutral securities such as money provides).

Well, all of that is just to say, I haven't got this properly worked out yet. But if, as I hope, you stick around and keep supplying questions and objections, we might get there yet!