|

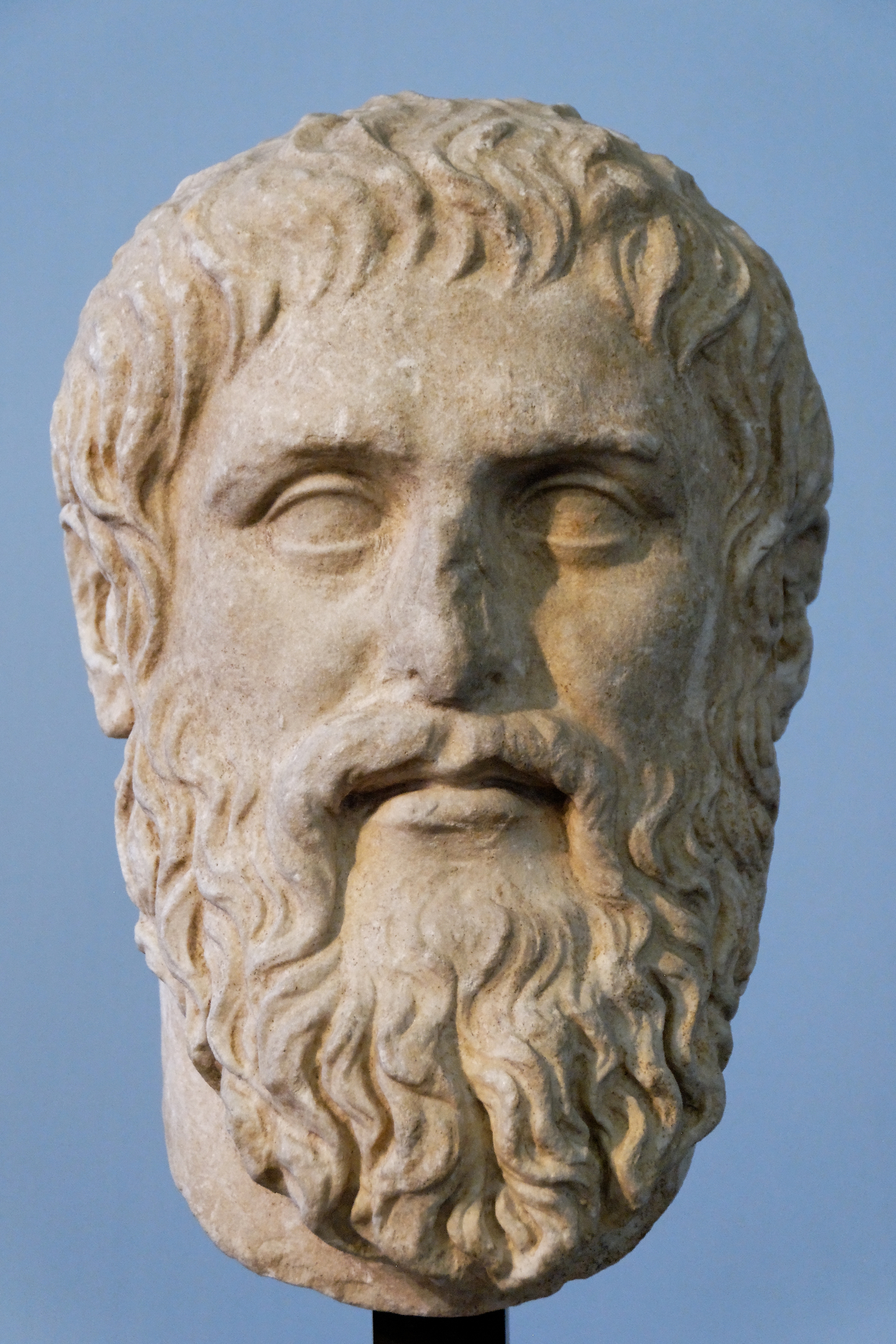

| image © Marie-Lan Nguyen Wikimedia Commons This post is part of a series on Plato's Republic. It is intended to continue the line of thinking summarized here. |

We have learned from the refutation of Cephalus that, when it comes to the matter of benefit at least, the untruth of the initial position consists in a kind of obviousness, and that thinking truthfully about benefit requires first thinking of it as something obscure and questionable. But very little in Platonic dialogs does not ultimately involve itself in the question of benefit. Certainly anything with a claim to worth has to be understood in the light of benefit. And we now know that this "light" is more like a shadow.

Does Cephalus sense a creeping horror in this cast of obscurity spreading over his view of things, and does he flee back to the sacrifices for fear of facing the uncertainty of his own way of life? This seems to be the standard reading of the character of Cephalus (Rosen, Bloom, and Annas all see him roughly this way), but if he really found Socrates so appalling, would it not give him pause, rather than provoke his laughter, to think of his son as "heir of the argument?" He so prides himself on having benefited his sons through a moderate guardianship of his wealth, that it is hard to imagine him suddenly wanting that inheritance to include a destruction of the very peace which that wealth is supposed to provide.

Since this interpretation (which I first learned from Rainscape's unpublished paper on the subject) contradicts the usual line on Cephalus, we need to analyze the action more closely, to see that:

Since this interpretation (which I first learned from Rainscape's unpublished paper on the subject) contradicts the usual line on Cephalus, we need to analyze the action more closely, to see that:

- Cephalus genuinely wants to benefit his sons, and cares more for their future happiness more than any self-indulgence.

- Cephalus's understanding of the benefit of money logically determines his sense of this bequest.

- As a reminder: the truth of the definition of justice concerns Cephalus in terms of the benefit of money.

In view of these three facts about the character of Cephalus, it will become obvious that it would be incoherent for Cephalus to depart out of some pusillanimous fear of the truth or narrow-minded conventionalism, and we will have to look for some other reason more in keeping with his character.

continued

continued