|

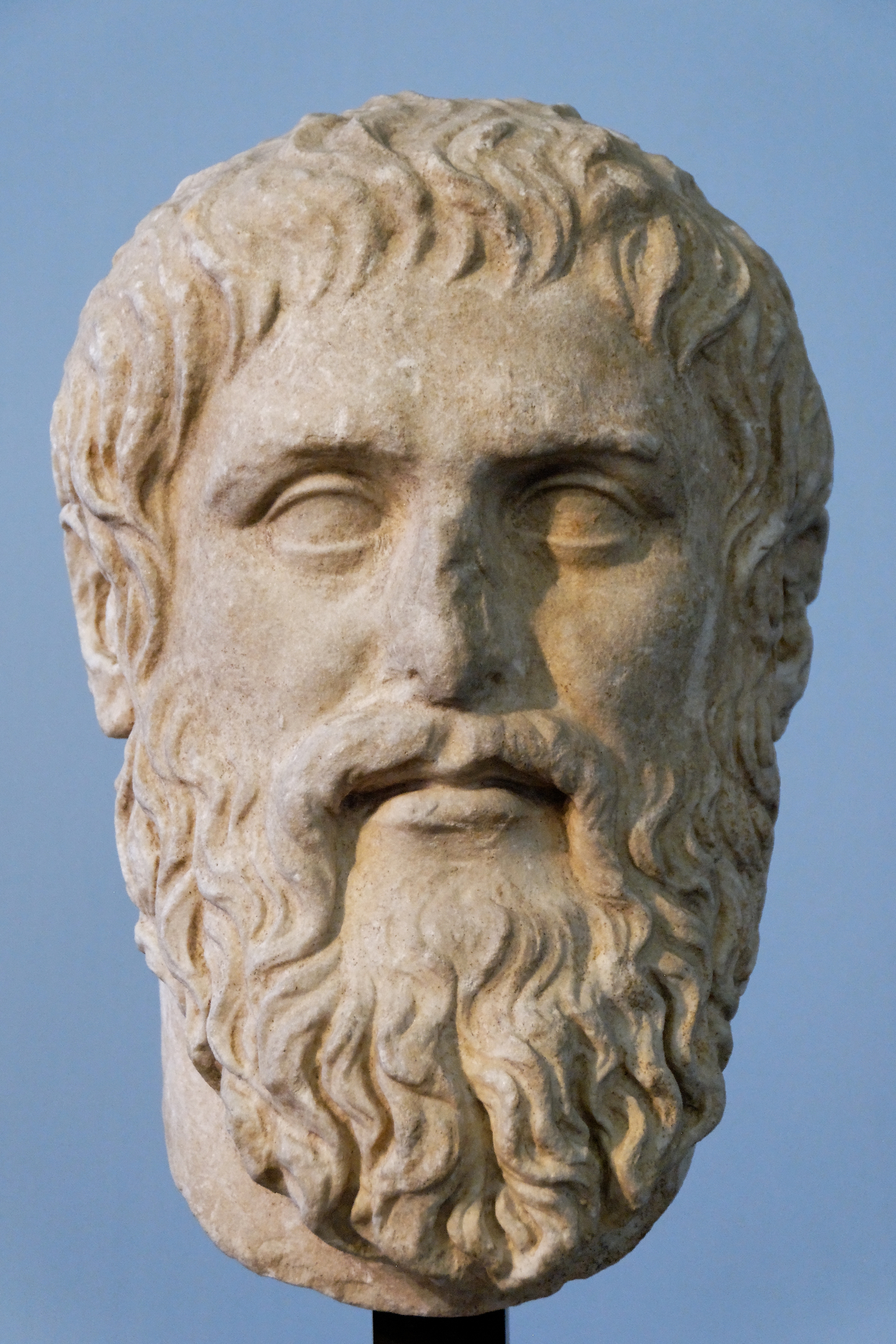

| image © Marie-Lan Nguyen Wikimedia Commons This post is part of a series on Plato's Republic. It can stand alone, but is intended to continue the line of thinking summarized here. |

In fact, if we follow up on Socrates's refutation as it is developed in the ensuing conversation with Cephalus's son, Polemarchus (not to mention Thrasymachus, we do find that benefit, especially with regard to the possibility of being mistaken about it, is a crucial turning point in the question about justice. According to Polemarchus, the hard cases of justice in which it supersedes the determinations of legal property are governed by the principle that "friends owe it to their friends to do good for them, never harm," and that justice "gives benefits to friends and does harm to enemies." So you would not give a deposited weapon back to an enraged friend because you know it would not benefit him but harm him to have it.

|

| I just can't think about the idea of the good when you look at me that way. |

Socrates's refutation of Cephalus does not turn explicitly on the question of benefit, but it does make clear that Cephalus cannot have seen the benefit of money, precisely in its relation to the idea of benefit, if he thinks that it facilitates justice by way of paying what is owed. For it equally facilitates injustice, if paying what is owed is sometimes unjust.

Thus the obstruction in Cephalus's view of the benefit of wealth is his own presumption of knowledge. He does not see benefit because he does not look for it in a place of darkness — in the field of his ignorance. Socratic wisdom is famously knowledge of ignorance. Here we see that this knowledge is a positive power, that orients the knower in the direction of what he would learn. To get the benefit of Cephalus's report, Socrates needs to place it in the light of something obscure. Benefit itself needs to be seen as something that somehow hides itself.

continued